THE SILK ROAD

Silk first began moving westward from China more than 2000 years ago, when the Parthians became quite enamoured with the soft, fine fabric. By about 100 BC, the Parthians and the Chinese had exchanged embassies and inaugurated official bilateral trade. The Romans developed an expensive fixation with the fabric after their defeat at Carrhae in 53 BC, and within a few centuries it would become more valuable than gold. The Romans even engaged in some early industrial espionage when the Emperor Justinian sent teams of spies to steal silk worm eggs in the 6th century.

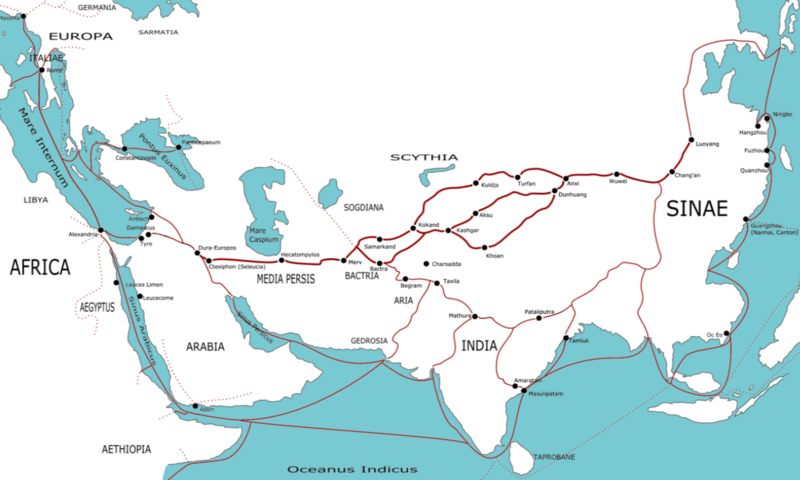

It took many months to traverse the 8000km Silk Road route, though geographically it was a complex and shifting proposition. It was no single road, but rather a web of caravan tracks threading through some of the highest mountains and harshest deserts on earth. The network had its main eastern terminus at the Chinese capital Ch’ang-an (now Xian). Caravans entered present-day Iran anywhere between Marv (modern Turkmenistan) and Herat (Afghanistan), and passed through Mashhad, Neishabur, Damghan, Semnan, Rey, Qazvin, Tabriz and Maku, before finishing at Constantinople (now Istanbul). During winter, the trail often diverted west from Rey, passing through Hamadan to Baghdad. Caravanserais every 30km or so acted as hotels for traders; Robat Sharaf northeast of Mashhad is a surviving example.

Unlike the Silk Road’s most famous journeyman, Marco Polo, caravanners were mostly short- and medium-distance hauliers who marketed and took on freight along a given beat. Goods heading east included gold, silver, ivory, jade and other precious stones, wool, Mediterranean coloured glass, grapes, wine, spices and – early Parthian crazes – acrobats and ostriches. Going west were silk, porcelain, spices, gems and perfumes. In the middle lay Central Asia and Iran, great clearing houses that provided the horses and Bactrian camels that kept the goods flowing.

The Silk Road gave rise to unprecedented trade, but its glory lay in the interchange of ideas.

The religions alone present an astounding picture of diversity and tolerance: Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, Judaism, Confucianism, Taoism and shamanism coexisted along the ‘road’ until the coming of Islam.

The Silk Road was eventually abandoned when the new European powers discovered alternative sea routes in the 15th century.

Lonely Planet, Iran, Lonely Planet Pub, 2008, PP 34